Sophia McDougall: Romanitas.

London: Orion, 2005.

075286078X.

xii + 452 pp.

This is a very enjoyable novel of alternative history.

The point of departure is in the late 2nd century, when the Roman emperor

Pertinax survives the

assassination attempt (which, in reality, succeeded) and goes on to

restore the strength of the empire with a series of reforms.

As a result of this, the Roman empire does not collapse under the external

pressures of the next several centuries, but manages to repel the various

invaders and slowly expands its territory, eventually turning into a huge

global superpower. This novel takes place in the present time,

in the year 2757 AUC, by which time the Roman empire

controls the whole of Europe; the northern half or so of Africa;

Asia as far as India and western Siberia; a good deal of North America,

and the whole of South and Central America. In addition to that, there is

a ‘Nionian Empire’, i.e. Japan, which controls much of SE Asia, Australia,

the various Pacific archipelagos, and the NW part of North America.

In between there is a somewhat weakened Sina, i.e. China. The southern half

of Africa used to be under Roman control but has recently managed to

secede.

<spoiler warning>

Set against this background, the novel is a gripping story

of intrigue in the imperial family. The emperor's nephew Marcus

has to flee from Rome as it turns out that the recent automobile

accident of his parents was really a murder, and that his own life

is also in danger. He stays for a while with a group of fugitive

slaves, but eventually learns that his enemies are accusing

his late father's friend and assistant Varius of having murdered Marcus.

The latter therefore decides to return to Rome, hoping to somehow

prove that he is OK and that he, his parents, and Varius are all

victims of a malicious plot. The challenge is how to reach his uncle

the emperor without getting into the clutches of someone who is

in on the conspiracy and would happily do away with Marcus.

With the aid of some of his new friends from the fugitive slave camp,

he eventually succeeds, the conspiracy is uncovered and the novel is

brought to a reasonably happy end.

</spoiler warning>

I found the book somewhat difficult to get into — the first

few chapters, although they were pleasant enough to read, didn't

really make me burn with desire to pick up the book again the next day.

However, by the time Una and Sulien meet Markus in ch. 6,

the story picks up momentum and evolves into a real page-turner.

In the last few days I was regularly staying up longer than usual

in the evenings.

Paranormal abilities considered harmful

The only thing that annoyed me about this novel are the paranormal

abilities of Una and Sulien. Una can read people's thoughts (if they

are located close enough to her in space) and to some extent even influence them;

see e.g. ch. 5, pp. 73–4; ch. 16, p. 282; ch. 21, p. 377).

Sulien has unusual abilities to heal people, especially things like

wounds or fractures; it isn't explained how he does it but it doesn't seem

to involve any tools or anything of that sort, only his touch.

These paranormal abilities of theirs are major elements of the plot:

without them, the story wouldn't be able to proceed the way it does now,

in several crucial places.

Now, there is of course nothing wrong in principle with giving people

paranormal abilities in a work of fiction. But, honestly speaking,

I cannot entirely avoid feeling that they act like a cheap deus ex machina here

in this story — they allow the author to set up much more thrilling

situations than she could do otherwise, because without these paranormal

abilities the characters wouldn't have any realistic chances of getting out

of these situations. Additionally, such paranormal abilities aren't really

something I would expect in a work of alternative history: for me, alternative

history means that the story is taking place in the same world that we are

used to, only that certain historical events turned out differently than they

really had — but these alternative outcomes must be within the bounds of

probability. I would somehow understand if the author had at least tried to

argue e.g. that because the Roman empire in her alternative history never collapsed,

this led to a faster progress of scientific research and consequently enabled some

people to reach these abilities that seem paranormal to us now; but she isn't

doing anything of the sort. There is no explanation of the exact nature, let alone the origin,

of these abilities, Una and Sulien seem more or less to have been simply born with them,

it isn't clear whether other people with similar abilities also exist, etc.

In short, it's a completely arbitrary plot device that doesn't even pretend

to have anything to do with the real world.

The present-day Roman world

For me, one of the most exciting things about an alternative-history novel

is to read how the author imagines the state of society and technology

in his or her alternative-history timeline. In this novel, the Roman technology

of the present day is substantially similar to ours; a few technologies from the

real world are missing in the novel, but not (as far as I can tell) vice versa.

Telephones and television are known, although they are consistently referred

to by Latinate words — ‘longdictors’ and ‘longvision’.

I guess this is meant to emphasize that in such an alterantive timeline, the

Latin language would naturally carry much more prestige than the Greek

(which is quite reasonable). There don't seem to be any mobile phones, however

(e.g. in ch. 6, p. 87, a person needs to go to a particular room to make a phone

call; and in ch. 23, p. 424, Gabinius is called to the phone by a slave,

which suggests that the phone is stationary).

Nor are there mentions of anything like the ubiquitous computers that sit

on every desktop in our real world.

They don't seem to have airplanes of the sort we know in the real world,

but there are ‘spiras’ or ‘spiral-wings’

which seem more similar to helicopters

(“flight using circling wings powered by engines”, timeline, p. 451). In the absence of flight, passenger

travel over long distances seems to be based chiefly on high-speed magnetic trains,

which seems to be one of the few areas in which the world in the novel is really

ahead of the real one, in which the network of magnetic railways is not nearly

so widespread and well-developed. But maybe they have passenger flight too:

see ch. 4, p. 66, “By magnetway or air he might have reached it in a day,

but Varius had already ruled out going anywhere near public transport.”

There exists a tunnel under the English Channel (ch. 5, p. 73) and another

under the Strait of Gibraltar (ch. 7, p. 92); a “vast suspension bridge”

is being constructed across the Persian Gulf (ch. 4, p. 58).

As for the languages, Latin is of course spoken widely throughout the empire,

but this doesn't mean that other languages have been entirely exterminated.

In the Pyrenees we still find the ‘Vascones’, i.e. the Basques, who keep their own

language and some of them don't even understand Latin (ch. 12, p. 205).

Marcus as a member of the imperial family and a likely future emperor has

been taught Greek, Chinese, and Japanese as foreign languages (ch. 12, p. 206) — apparently

Greek still has some prestige as a classical language (but “ ‘Greek's only good for writing’ ” says

Marcus on p. 206 — perhaps it was dead by then, like Latin or ancient Greek are now in the real world?),

while the other two would of course have been important for foreign policy.

(He also knows a few words of Quechua and Navajo, p. 206.)

Slavery

Slavery is one of the major and recurrent themes in this novel.

It is still a perfectly ordinary and widespread thing in the Roman empire at

the time the story takes place, although there seem to be concerns that the number of slaves is decreasing

because there aren't as many wars as there used to be (most of the world is

already conquered, and the situation vis-a-vis Japan, Rome's chief rival,

has been fairly stable for some time).

See ch. 14, pp. 265–7, where Dama recounts his experiences as a slave employed in

construction work, for an example of how slavery might function in such a relatively

modern economy. The extent to which Roman society and economy rely on slaves

is described by Varius in ch. 4, p. 55, but of course his arguments

inevitably seem specious to a reader from our real world, which we all know

to work well enough without outright slavery. I wonder to what extent

slavery could really be included efficiently into a really modern economy,

and whether it would accelerate the growth of any of the traditional sterile

economic indicators, such as the GDP. The only large-scale experiment with

slavery in a modern economy that I can think of at the moment

is Germany during the WW2,

but I'm not sure to what extent this can be extrapolated.

Marcus' father, before his murder/accident, was planning to

abolish slavery should he succeed to the throne, and Marcus adopts the same

resolution for himself. In fact his uncle, the present emperor, is himself not

really opposed to this idea, but prefers to leave such tumultous reforms

to his successors (ch. 24, p. 431).

Crucifixion is still a common punishment for slaves, just like

in the ancient times, although they have modernized it somewhat by using a

mechanical cross which pierces the limbs automatically and then raises itself up,

so that the executioners don't need to do anything else but tie the victim onto

the cross with ropes; nor do they seem to whip the victim beforehand.

There is a fairly graphic description of the whole

process in ch. 3, p. 19, and one of the more prominent characters in the story, Dama,

is in fact a crucifixion survivor — he was rescued from the cross by some

passers-by after spending some seven or so hours there, and has survived although

his limbs are of course largely crippled (ch. 12, pp. 416–7).

(Ch. 12, in which Dama is first introduced, is excellent this way — little by

little it drops hints that guide the reader's attention towards Dama's curious

disabilities, and only slowly does it become clear that this is due to a crucifixion.)

(Incidentally, if you want a really detailed and gruesome description of an old-fashioned

and brutal execution, and in a highly respected literary work to boot, I recommend the impalement scene

in The Bridge on

the Drina by Ivo Andrić.)

Incidentally, the web seems to be somewhat undecided about the spelling of ‘crucifixion’.

Dictionaries, e.g. dictionary.com, allow only

‘crucifixion’, which also seems to be the most common on the web, with about 4.6 million

hits on Google. But ‘crucifiction’ is also quite common, with about 2.0 million hits.

In addition there are 50000 hits for ‘crucifixtion’.

There's an interesting monologue by Gabinius, the scheming and extremely rich man

who is one of the chief villains of the book. His grandfather had been a slave:

“ ‘I'm not — I won't be ashamed of him, either.

He was a wonderful man. I'm the first one of my family who can stand for the Senate.

And I'm going to. This, this — only in the Empire can that

happen. Varius, the only places in the world where there isn't slavery of

some kind are the places where everyone, to all intents and purposes, is a slave.

We're the only ones who give them the chance to work their way out of it.’ ”

(Ch. 11, p. 195.) It's remarkable how these same disgusting old arguments

are the same in all ages and all parts of the world. Consider the idea that

people must ‘work their way out’ of the lower class — some time

ago I read nearly the same ideas in a book titled

The Pro-Slavery Argument,

published in South Carolina in 1852. Those defenders of slavery in the southern U.S. likewise

claimed that they are practically doing the slaves a favour by forcing them to attain

work habits, and that it will be reasonable to consider the abolition of slavery only

after the slaves get far enough along this path of (work-)ethical development. Other

parts of Gabinius' argument remind me very much of those put forth nowadays by

proponents of cut-throat capitalism, the free markets, meritocracy, etc., etc.

If you change just a few of Gabinius' words, you could get a classical cold-war era

pro-capitalism argument: “The only places in the world where there isn't exploitation and inequality

of some kind are the communist countries where everyone, to all intents and purposes,

is a slave (of the state and Party).” Which, of course, is complete and utter bullshit.

It is completely absurd to imply that a system in which everyone is left to his or her own devices and therefore

the vast majority of the people are wasting away their whole lives in work and insecurity

for the benefit of a small handful of the rich

is somehow better and more conducive to freedom than a system in which the state

helps the people, protects them from themselves as well as from each other, and

keeps the economy under control to make sure it is used for the benefit of the whole

society rather than just its wealthier parts.

Marcus' parents planned “to set up a system of free healthcare for slaves,

so that their owners would have no reason to abandon them when they became sick.

[l. . .] Leo [Marcus' father] had wanted the companies which relied most heavily

on slavery to pay the most.” (Ch. 4, p. 58.) Maybe I'm biased,

but this reminds me awfully strongly of the periodic debates on universal healthcare

in the U.S. Am I just being blinded by my own political prejudice, or is the

author inviting us to contemplate the parallels between ancient Roman slavery

and the cut-throat capitalism of our modern age? (Although, of course, even if we

do make such comparisons, they will not all lead to the identification of similarities.

There are also some differences. Reading a portrayal of slavery in a fictional modern economy,

such as the one in this novel, and comparing it with the condition of workers in the

real world now, one cannot help concluding that the slaves are in a significantly

worse situation after all.)

Una, who, like probably many other former slaves, can't read very well,

is slowly struggling through an old copy of the Aeneid.

“Marcus said stiltedly, ‘Are you still reading the book, the Virgil?’/

‘It's propaganda.’ ”

(Ch. 16, p. 283.) And it's true, of course; it is in fact one of the

things that also annoyed me when I was reading the Aeneid.

But it's interesting how now, since the Roman empire has been gone

for so many centuries, the fact that it's propaganda isn't really the first

thing we think of when we think of the Aeneid. I wonder if

the same thing happens to other authors once the causes they espoused

become sufficiently long dead and forgotten that people can read their works

dispassionately. Will we be able, a thousand years from now, to read Kipling

the same way we read Virgil now?

Miscellaneous

The author admits upfront (p. vi) that this book is intended

to be the first part of a trilogy. It can stand by itself, in principle,

but the end is far from fully satisfactory and it is clear that

things have been laid out so that the story will have the opportunity

to continue in the next novel. For example, we don't learn the

ultimate fate of Delir and the rest of the escaped slaves of Holzarta

after they had to evacuate their camp, pursued by imperial agents

(ch. 24, pp. 436–7). Marcus has been designated heir to the position of emperor, but, of course,

since his uncle (the present emperor) is still alive, there are any number

of obstacles that the novelist may yet choose to place between Marcus

and the throne. Nor can we be quite sure if the relationship between Marcus

and Una will go on well, how the society around them would react to it

(given that she is a recently freed slave), etc. Marcus' cousin and rival Drusus

remains at large and apparently unsuspected of his complicity in the plot (ch. 24, p. 442);

I guess he is likely to come up with some further mischief in the future.

I look forward to reading the sequel, which, according to amazon.co.uk,

will be called Rome

Burning and will be published in the spring of 2007.

P.S. Three cheers for the publisher for setting the RRP of the hardcover

edition at a mere £13 — this looks like a remarkably

decent price in these crazy times when more and more publishers seem to consider

it reasonable to price their books at insane things like £30.

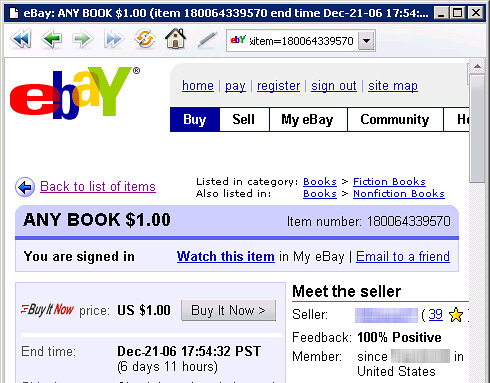

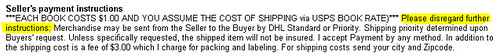

I, of course, wouldn't be the scrooge I am if I didn't go one better

than that — I bought a mint copy of the book on eBay for a measly

£2.5 :-)

P.P.S. I know I will fry in hell for making remarks like this, but

there's a photo of the author on the back flap of the dustjacket.

She is young, slim and pale — very pretty.

[Update: I've now read Rome Burning. I liked it even better

than Romanitas; see my post about it.]

Labels: books, fiction, Sophia McDougall